Why 'tough guy' policing fails

Law enforcement's reaction to widespread protests this week could be summed up in an order that was handed down from President Donald Trump to the nation's governors during a phone conference Monday.

"Law enforcement response is not gonna work unless we dominate the streets," Trump told governors. "They're gonna run over you, you're gonna look like a bunch of jerks. You have to dominate," he repeated. "Most of you are weak," he added.

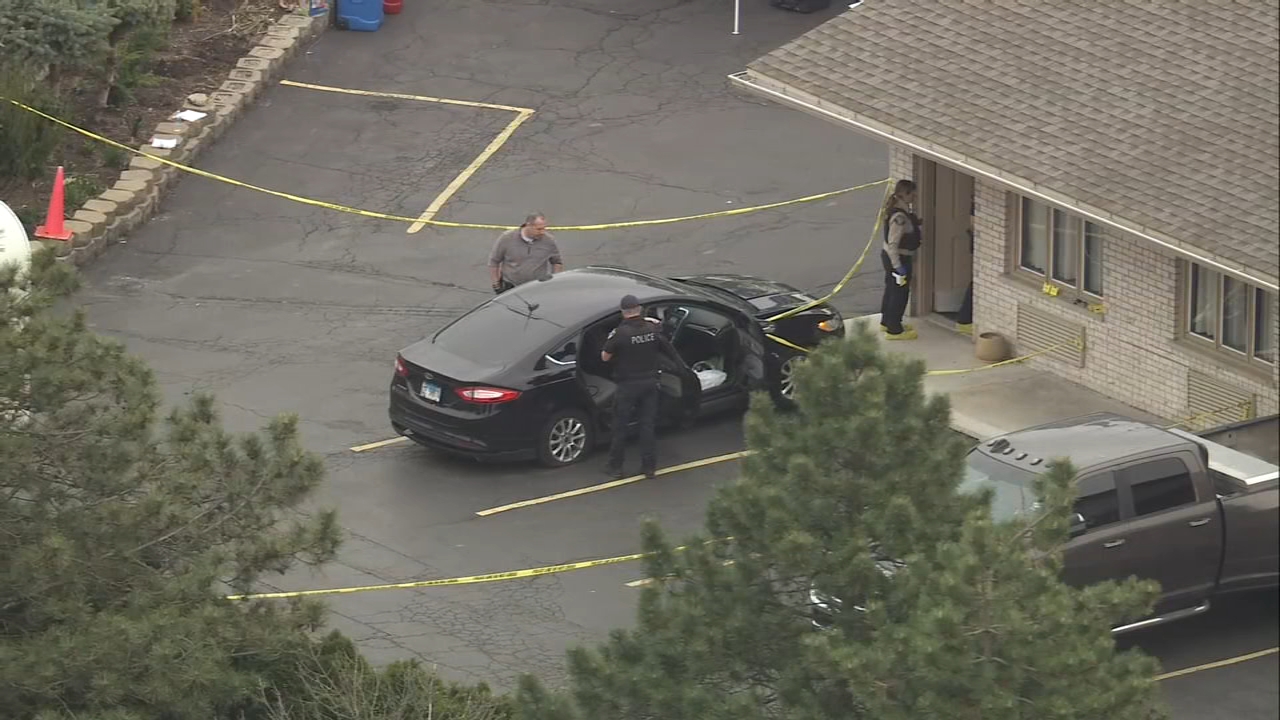

The approach reverberated in the streets. In cities across the country, police officers outfitted in riot gear and gas masks clashed with demonstrators, dispelling them using tear gas and rubber bullets or striking them with police batons. In Washington, D.C., a National Guard helicopter flew so low over protestors that it sprayed them with rotor wash, a scare tactic used by military aircrafts in war zones. As protests escalated, individuals threw rocks and glass bottles at officers and lit police vehicles on fire.

"What the president said on Monday was the ultimate exhortation of 'tough guy' policing," said Bob Edwards, a sociology professor at East Carolina University, who studies social movements.

So-called "tough guy policing" is paradoxical, Edwards said, because hostile treatment of protesters creates and escalates the very behavior the police are trying to suppress.

Police departments send a message to protesters from the moment they direct officers on how to suit up for the day.

Riot gear, gas masks and military vehicles send a message to protesters, Edwards explained. While officers may think riot gear simply means being prepared, protesters interpret that gear as a signal of the amount of force officers intend to use on them. Whether or not it's their intention, a police officer in a gas mask is sending a signal to the crowd that he intends to use tear gas.

"The signals get miscommunicated," Edwards said. "As opposed to the police thinking of them as acts of preparation, riot gear and gas masks are in themselves acts of escalation."

The tough guy approach doesn't leave space for distinguishing between a small number of opportunistic individuals seeking chaos and the vast majority of aggrieved demonstrators responding to a police officer kneeling on George Floyd's neck until he died. Instead, peaceful protesters, bystanders and journalists are policed in the same way, "often with hostility and force," Edwards said, "which makes them angry for being treated in way they don't deserve."

The result is a vicious cycle of escalation.

We've known for decades that 'tough guy' policing doesn't work

"Best practices in policing these days is to de-escalate, not escalate," said John Noakes, an associate professor of sociology at Arcadia University, where he researches the policing of political protests.

It's hardly a novel idea.

Three federal police commissions between 1967 and 1970 investigated violence at protests and found that escalation tactics like tear gas and mass arrests were counterproductive, often creating the violence they were intended to stop.

City government and police authorities should "eliminate abrasive policing tactics," recommended the bipartisan Kerner Commission, which was appointed by President Lyndon Johnson after protests in cities including Newark and Detroit turned violent in 1967.

But despite decades of recommendations to police to practice de-escalation, that guidance has not been adopted in a widespread sense.

A Pentagon program continues to transfer military weaponry like bayonets and grenade launchers to local law enforcement departments.

Community policing, which relies on building relationships and trust between officers and the neighborhoods they serve, has eroded, Edwards said. "People in the community, and also protesters, often see the police as an occupying force," he said. "Both groups seem to almost live in different worlds."

Noakes pointed to cities where police have kneeled with protesters or held up Black Lives Matter signs. "That only works if you built a relationship with the community over the years," he said.

In Camden, New Jersey, where protests have remained relatively peaceful, former Chief of Police Scott Thomson, pointed to the effort the force had made to build trust with the community long before the George Floyd protests.

"What we're experiencing today in Camden is the result of many years of deposits in the relationship bank account," Thomson told Bloomberg Businessweek.

This week's protests may also be especially fraught because unlike demonstrations on climate change, vaccines or abortion, for example, demonstrators are protesting the police themselves, including calling for agencies across the country to be defunded.

"The police have a much harder time responding to protests that are about them," Noakes said. Police departments also talk with one another, he explained, and may view acts of violence against officers at companion protests in other parts the country as raising their own perceived threat level.

While there have been widespread examples of tough guy and abrasive policing tactics used in cities across the country this week, law enforcement is not a monolithic institution and some departments are doing better than others.

"There's a fair amount of variation across how individual police departments do their job on a daily basis and how they do their job in unusual times like this," Edwards said.

"Reform gets adopted in an uneven way."